Whether she’s breaking egg shells on the sidewalk or weaving used clothing into huge billowing shapes, Betsy Lohrer-Hall is constantly exploring her relationship with environment and community, and gently encouraging those who experience her work to examine their own ideas about things. Often process oriented, her work does not fit neatly into narrow categories, moving fluidly from conceptual to installation, from sculptural to collage, and even into video and performance.

Sander: Tell me about your contribution to Quiet Life: The Botanical World (at Santa Ana College at Santora).

Betsy: I have always been a nature lover and have made work over the years with and about plants, so sometimes people think of me when they are going to have an exhibition about plants. This time, Mayde Herberg contacted me about the show and I realized that my current life, sadly, is pretty distant from the natural world. I haven’t even gone camping in the last year or two. My project for the show is really about this distance that I feel between myself (all of us, really) and the natural world sometimes, and this can cause a lot of problems.

One of the things I do to make money is paint murals in peoples homes. I got to thinking about how we surround ourselves with symbols of the natural world (I often paint flowers and landscapes)… while we are decorating with natural images (on curtains, sofas, clothing, etc). In many ways the distance between cause and effect of our impact on nature is becoming increasingly obscure in our consciousness. A friend of mine recently noted that if we knew the true price of oil, we would realize that we couldn’t afford it – financially, morally, or environmentally. So, all this being said, my piece is called “Phytoplankton: My Deep Understanding and Intimate Experience with the Tiny, Tiny Plants of the Sea” and it is large scale, quite-probably-incorrect depictions of phytoplankton on shower curtains.

Sander: How does this relate to the feelings of distance?

Betsy: hmm. well, I am not sure how to articulate this, but sometimes I think that all of our use of symbols, semiotics, while very efficient (and fascinating to study and explore), might cause us to overlook the finer points of the larger picture. Does this make any sense?

Sander: Yes, absolutely. “The map is not the territory.”

Betsy: I like that… the map is not the territory. I like maps as drawings, and they are very useful, but you can’t see what color the blades of grass are, or what kind of birds are there. I suppose one of the things I have always been interested in doing is noticing the tiny little gems in life that are often overlooked. Our contemporary culture (at least what I know of it here in my experience of the world) is very fast paced and not as contemplative as I like to be

Sander: In your work, you’re revealing something we don’t normally see, and presenting it in an unusual context. That relates to a number of pieces of yours that I’ve seen.

Betsy: Yes, actually the phytoplankton are incredibly beautiful. Interestingly, some of them are quite deadly, too. This dichotomy seems to pop up in my work too. I am also interested in what you get from the pieces of mine you have seen…

Sander: Well, I’ve seen two and read about a third. The first was the map you made of Los Angeles. Can you talk about that?

Betsy: Map of Los Angeles? Do you mean the City piece at the 2nd City Council Art Gallery + Performance Space?

Sander: Yes.

Betsy: Well… that was (is) a very process-oriented piece as several of my projects tend to be. I am interested in activities taking place over time. I live a few blocks from the beach here in Long Beach and I started picking up plastic beach trash when I was down there after a run or walk. I found it pretty shocking: First that there was so much of it and such a variety, and also the fact that as we all know plastic isn’t biodegradable. It really got me thinking about our throw-away habits in this country. it is staggering. So I started amassing these collections from various trips to the beach. I set a rule for myself that I would only include what I could carry in my hands.

Sander: Why was that important?

Betsy: I wanted the collection to be indicative of one person’s activities over sporadic visits to the shore. I felt that this would give some sense of the vastness of the issue and the impact of one person’s actions in regard to the issue. It was an interesting experience at the beach. Some people asked in wonder why I would pick things up off the beach like that. Others handed me things and smiled. I have done several projects that incorporate collecting in some way. For me, this is a way of seeing/listening to our community. These remnants are a form of expression.

Sander: When you were collecting did you have a clear idea of when you’d have enough material to start working with it, and did you have a plan for it?

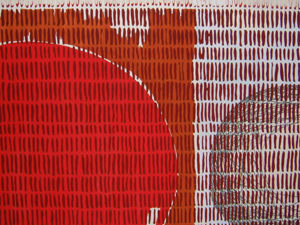

Betsy: When I started collecting, I was collecting only plastic lighters. I made rust prints with them on paper. Then I started collecting bottle tops. As with most projects, I got restless with such tight parameters and started collecting all manner of things. It was amazing what I discovered. I didn’t have a clear idea of what I would do and I am not sure exactly how it evolved into a city made of plastic discards, but that is what happened. I enjoyed the process of laying out the installation on the floor — very much like a painting. Ritualistic in some ways, too, and all the dots from the bottle tops reminded me of Tibetan sand mandalas or Aboriginal Dreamings.

Sander: Had you layed it out before, or was the 2CC installation the first time you realized the piece?

Betsy: I showed City for the first time at Soka University art gallery in Aliso Viejo. The 2CC show was the second time (and very different in some ways — bigger, more varied, and, as my dad noticed, less red).

Sander: How did you get involved with Soka?

Betsy: I am not really… Daniel duPlessis was curating a show for their gallery and he put out a call for artwork addressing concepts of landscape. My City piece was just a baby then, but I submitted slides anyway. When I got accepted, it gave me the impetus to fully realize the piece for the first time

Sander: Well, to answer your earlier question, I was really engaged by the piece.

Betsy: That is great. I am always interested in people’s responses… What was it that engaged you?

Sander: I felt that there were certain immediately self-evident things about it but, as I spent some time with it, more was revealed. I felt that it was evocative, and created a dialog with me, rather than telling me something. I saw that the plastic was worn and, although I wasn’t sure, guessed that it was from the beach. Also, the scale of it really hit me. That it was of the City… well, that seemed to address a whole other level of meaning: A city of trash, a city of plastic…

Betsy: Yes, all that plastic… a little scary. I am glad that you felt that the piece was evocative and created a dialog with you. This is important to me. I prefer that my pieces have layers of metaphor and are open to interpretation. It’s like… I am not sure how to say it. It is like tickling new thoughts into being rather than having an agenda. I would rather that the viewer have a realization experience (even an experience I haven’t planned at all) than to tell them what to think.

Sander: That’s what the best art does, I think, or at least the art I like best.

Betsy: Me too.

Sander: Another aspect of the piece, one I found really challenging, was its fragility. Being set up on the floor, nothing keeping it protected or together, made me feel very protective of it. I found that to be both disturbing and somehow pleasing.

Betsy: Nice observation. A lot of my work is extremely fragile and, in many cases, temporary. On one hand this is very hard on me because it is like constantly facing mortality, (but I also think it is really important for me to face it and it is where a lot of painful-beauty lies.) On the other hand, there is extraordinary freedom in this same facing of evanescence.

Sander: I went back to see it again, some days later, and wondered if you’d just sweep up all the pieces or pick them up one at a time.

Betsy: I didn’t pick them up one at a time, but they are sorted by color and size, to some extent. That will make it a wee bit easier to set up again (like having an organized palette) Some have suggested that I glue the pieces down to boards or something, but even though it is physically demanding and time consuming to set up the installation, to have a permanent arrangement would change the work completely.

Sander: I agree. The fragility and impermanence of the piece was a huge part of my experience.

Betsy: Sometimes it seems like my work doesn’t have the same consistency as, say, someone who paints portraits of people her whole life. The medium changes with the idea.. but there are some underlying consistencies, definitely.

Sander: Well, this leads me to another project you were involved with… The one where you were using old, donated clothes. I didn’t see this one, but I remember being amazed by the idea. Can you discuss that a bit, how it unfolded, and the result?

Betsy: That project was called Seems Familiar and was a collaborative project that I did with Edith Abeyta. She and I had been asked by Robin Hinchliffe to do a two-person show in San Pedro at what was called at that time the White Box Gallery. We had never met, and so leading up to that show, we worked together in my studio a bit. Instead of a two person show, we ended up with Paper Trail, a two person collaborative installation where we invited gallery visitors to participate too. From that show, via a couple of stops along the way, we came up with Seems Familiar at the Acorn Gallery in Highland Park. For Seems Familiar, we collected cast-off clothing from everyone we knew (and some we didn’t). The installation consisted of three large bee-hive-like weavings that hung from the ceiling, made entirely of the clothes. Edith and I had a wall of notable clothing, too, as well as folded stacks of extra clothes on the floor. We had recorded stories and memories about clothing which played in a continuous loop during the show. Gallery visitors were invited to bring in clothes, exchange clothes, share a story, etc. Used clothing is rich with possibilities and it was also amazing how much clothing people had to give away (some of which still had store tags on it.) The weavings were like a community of sorts.

Sander: Well, this reminded me so much of your City piece. Not the nature, or practical aspects of it, but the heart: Taking the detritus of our lives and transforming it into something else, something beautiful, or meaningful.

Betsy: Oh, yes… what a great way to tie the two together. A lot of my work is about reclaiming. Someone told me once that my work feels hopeful. I thought that was interesting.

Sander: Does it feel hopeful to you?

Betsy: I am not sure I was aware that my hopefulness was coming through in the art

Sander: Well, I guess the hopefulness is shown in the idea that you can take something that’s cast off and reclaim it, reclaim it as art and, in a more metaphoric way, I think we all feel cast off, and want to be reclaimed

Betsy: That is nice. I liked some of the SPIN sculptures in part because of the reclamation aspect (and their playfulness.) I don’t always manage it in my work, but I enjoy art that has an element of the ridiculous or humor.

Sander: Strange, but I don’t remember feeling that way. I don’t mean that as a criticism, by the way. For example, in your Soundwalk piece, Breaking Codes, I think some people just thought you were a nut, but I really was fascinated by your process.

Betsy: Definitely some thought I was a nut (myself included, about half way through.)

Sander: I loved watching how you tapped each egg shell, almost testing it, before you got that satisfying crunch.

Betsy: That piece was a bit scary for me because I felt like it was something I had to do and felt very strongly about, but it was hard to accept that some people would simply see it as absurd. This being said, others responded to it very intensely and got a lot from it, from what they told me.

Sander: Tell me about that feeling of compulsion.

Betsy: [laughs] It is a feeling I have known well. [smiles] Sometimes an idea presents itself to me and it is very clear. Clear in general direction, but not necessarily in concept (until later) or even in material form. But I feel compelled to pursue it diligently. It’s just the way I am wired. It is a very emotional, but also deeply satisfying journey, but something has to incite me to be willing to take the risk

Sander: In Breaking Codes, what was the core idea, and how did you pursue it?

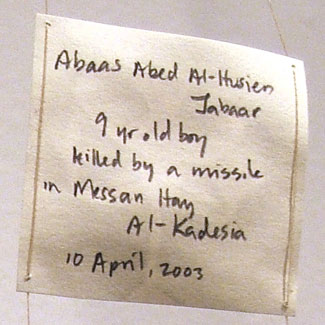

Betsy: I started with fragility — eggshells — which I was collecting (with help from friends, family, and the Coffee Cup Café) for a long time, drawn by the color, the texture, the quality of light on form, and … the sound. At first (for well over a year) I had no idea what I was going to do with the shells. I am not sure how to put this one into words, because it really arose intuitively in a lot of ways. Eggshells are rich in metaphor on their own. Several viewers related to the idea of the feminine, though that wasn’t my guiding principle, really. I was thinking more about how we, of different cultures and religions and languages implore our conception of God to help us determine what is right and, for me, tapping the names of God — of many religions and in many languages — in Morse code with the eggshells was a way of working through my distress over the wars and mistreatment of human beings by other human beings that are happening right now. Most often, the eggshell cracked before I got through a whole word, so I had to start again.

Sander: So each eggshell was a prayer?

Betsy: Yes, each was a prayer of sorts. I loved it when someone asked if I “took requests” and I said yes. He said “how about ‘jehovah’,” and the eggshell I used made it through the whole word.

Sander: I didn’t know about the morse code aspect of the piece. I just saw you kneeling there, cracking eggs. So, in a way, this relates to what I said about your City piece, that some things are self-evident, and other things less so.

Betsy: Yes, maybe part of this was lack of foresight regarding the lighting. I had a diagram for understanding the code — a beautiful design actually — on the sidewalk, but it was in the dark after the sun went down. In some ways this was o.k. too

Sander: How did you know when the piece was finished? When you ran through all the names, or when you ran through all the egg shells?

Betsy: Actually, I went through all the names I knew, many many times. I was surprised that also some words came up as I was doing it that were not what I anticipated, but very insightful in terms of sending up a prayer or thinking of a conception of God. I went for the whole five hours of the Soundwalk. A few minutes after 10pm, Shelley [Rugg-Thorp, one of the organizers of Soundwalk - ed] told me we were all done. I still had more shells, but decided to stop. There were several people who had come back to the spot because they wanted to talk with me about the piece. There was one man, from Poland I think, who actually asked if he could take some of the egg shards. He was so happy that he had a bag with him and filled it full. I would love to know what he did with them. The whole process felt intense, but really good

Sander: Do you feel that you have a rich spiritual life? I know that’s probably a strange question, but it seems that there is a component of this in your work…

Betsy: Not a strange question at all. Definitely, but it feels strange to even talk about it. The words (revisiting the idea of symbols) don’t even come close to all that is implied by spiritual. This being said, the artmaking is very much akin to spritual practice, including exploration of flaws and shortcomings. [smiles]

Sander: I think that with any creative process there is an element of mindfulness, of attention, that’s required. These things parallel spiritual practice.

Betsy: True, and as I said earlier, for me there is an element of accepting mortality. With this, there is also the idea that, like the eggshell, we are much more than our husks. With artmaking there is also the element of being willing to search in the unknown (unknowable?). I was just listening to a CD by Krishnamurti and he was talking about how, as soon as we claim to be “Catholic” or “Hindu” or whatever, we are creating division, and where there is division, there is conflict… interesting thought

Betsy: Quiet Life is at Santa Ana College Gallery at the Santora Building in Santa Ana… Through May 5. (group show)

Betsy: Upcoming… I am going to be in a fun group show called “PlayItGround” curated by Yong Sin at Don O’Melveny Gallery on Wilshire. It opens March 17.

Very thought-inspiring. Keep America Beautiful!

[...] Betsy Lohrer Hall is a conceptual, mixed media artist living in Long Beach, California, USA. [...]